For more serious crimes, the punishment was usually execution in one grisly form or another. I won't go into detail about these methods because some people might inexplicably find it unpleasant to read about, but if you do have a perfectly understandable curiosity about practices such as drawing and quartering, you can just look it all up yourself. Sorry, but I'm here to talk about prisons.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, crime rates soared throughout Europe as populations increased, economies suffered, and rural residents fled to the cities to try to make a living. If they couldn't succeed there in feeding themselves and their families by legal means, many turned to illegal ones. The traditional penal systems started becoming unmanageable, and it was apparent that something was going to have to change.

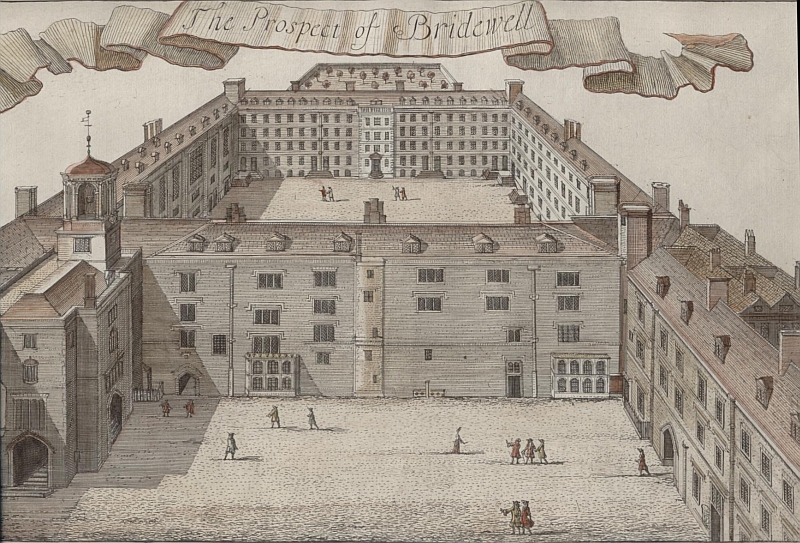

That change started in London in 1553. In that year, Bridewell Palace, originally built for King Henry VIII in 1515, was donated by Edward VI to the city, which revamped it into a prison facility for petty criminals. That category included "vagrants," i.e., homeless people. Instead of being subjected to brief public humiliation, the prisoners - all of them poor - would instead be both punished and (so it was thought) reformed through a period of enforced hard work, for which they would be paid a small wage. More than half of the prisoners were also beaten. And yes, the opening of Bridewell Prison was indeed considered a reform; after all, it gave the benevolent state the opportunity to help the poor to help themselves!

One actually beneficial innovation at Bridewell was providing services to homeless children. Operating as the prison's charitable component, which was called a "hospital," Bridewell provided to its apprentices a rudimentary education and a course of training under masters in useful trades.

But of course, it was the "reformist" system of managing indigent populations through incarceration, and not necessarily the "hospital" idea, that soon spread throughout England and the rest of Europe, along with the name "Bridewells." I'll put in my own two cents here by saying that the system still sounds shockingly familiar to me as a 21st-century American.

And then things got even worse in the prisons when the Black Plague swept through Europe in the mid-1500s. Aware that the terrible sanitation conditions (see my B for Bathrooms post) and cramped living quarters conditions among the poorer classes quickened the spread of the outbreak, the Powers that Be hit upon the novel idea of sending debtors to prison in vast numbers. After all, the more poor people who were locked up, the fewer there were still out on the streets to spread disease, possibly even (OMG) to the upper classes. In the prisons, the reasoning went, the only people they could infect was each other, so... really, how much of a loss could that be?

The Plague eventually died out, carrying with it about a third of Europe's population. But the practice of debtors' prisons persisted into the 19th century, when it ensnared the father of the young Charles Dickens, among countless others.

|

| "Debtors Prison," by William Hogarth |

Terrible conditions. Awful to think young children and first time offenders cooped up with hardened criminals.

ReplyDeleteI didn't realize prisons were a relatively recent invention... Makes perfect sense, though; populations were smaller, crimes fewer and far less serious. Still, as you say, the whole Bridewell concept sounds eerily familiar. I'm not an expert on penal systems, but it seems obvious we're doing it wrong. Ooooh, and how chilling that debtors' prisons stemmed from the Plague!

ReplyDeleteGreat, great post, Susan. This series of yours has me spellbound :)

Guilie @ Life In Dogs

I'm relieved to hear that the homeless children got access to some vocational training and were given a chance to improve their lives.

ReplyDeleteYes, the system did have its benefits as far as the apprentice program, but as far as the prison, it was clearly an idea for reform that ended up going very, very wrong.

DeleteIf I had a choice, I would definitely choose to be in prison now rather than then.

ReplyDelete~Ninja Minion Patricia Lynne aka Patricia Josephine~

Story Dam

Patricia Lynne, Indie Author

I'm not sure anyone sane would make the other choice, Patricia!

DeleteSo they had prisons a couple of centuries before they had an actual police force... go figure :P Punishing the poor for being poor is still pretty much alive too.

ReplyDeleteAlso, cute dog!! :)

@TarkabarkaHolgy from

The Multicolored Diary

MopDog

And of course, there's the stacked system of setting money bails for pretrial detention. If you have money, you can make bail, keep your job, stay with your family, and help prepare your defense. If you don't have money, tough luck.

DeleteI like the way you started w/ "Orange is the New Black" to introduce your topic today. The history of incarceration in most cultures is troubling and inhumane. Glenda from

ReplyDeleteEvolving English Teacher

Indeed it is, Glenda. I haven't done a survey, but I'm still pretty sure that poverty is still the distinguishing characteristic of most prisoners worldwide.

DeleteI heard a part of this when I visited Kilmaiham Gaol in Dublin last September. There too, in the first few decades of the jail (it was built in the 1700s) the majiority of the population were debtors.

ReplyDeleteThe guide explained to us as forced labour first, then forced silence were considered methodes of redemption.

I have to say, 1800s ideas about reformation sound quite weird to me...

@JazzFeathers

The Old Shelter - Jazz Age Jazz

Well, Sarah, I guess that allowing for any form of redemption at all seemed like a pretty radical idea at one time!

ReplyDeleteI am actually in the book Orange is the New Black. Well, very briefly. Prison is a big yuck. But, at least, no one is contracting the black plague, and no one is getting drawn and quartered.

ReplyDeleteOkay, you have definitely captured my attention!! Why, pray tell, are you in this book???

Delete