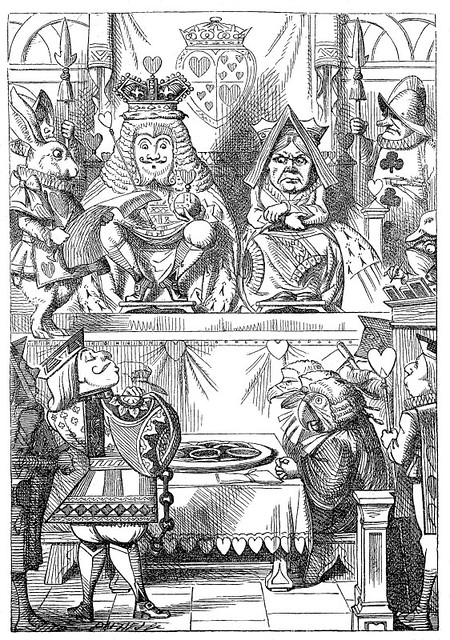

The answer: It isn't. The Mad Hatter had no idea what the answer was to his own riddle, and that's because it wasn't a real riddle, the answer to which would have been based on a clever pun; it was just a nonsensical question without an answer, which infuriated the practical-minded Alice.

On the other hand, there are such things as questions that may sound nonsensical, but that are, in fact, so sensical that even Alice would approve. Here's one: why is the process of performing revisions on a novel like the process of preparing an argument before the state Supreme Court?

I guess I should explain. I have two jobs: (1) being an appellate lawyer, which consists of writing briefs and orally arguing cases, and (2) writing novels, which consists of writing novels. The first job brings me a paycheck; so far, the second one doesn't.

For the past week and a half, I've been in the throes of revising my latest novel. In the process, I've come to realize that I managed to create the characters and narrative, and write an entire first draft, all without being aware of some major themes I'm now discovering. I was trying to understand how this could even be possible, when - eureka! I discovered an analogy to my other job.

When I prepare an appeal for the lower of the two state appellate courts, I do research; I analyze the issues; I organize my arguments. By the time I've written my brief, no one knows my case the way I do.

Depending on how the case is decided by that court, it has a small chance of eventually winding up, one way or another, in the higher-level state court, which always entails my not only writing a second, more focused brief, but arguing the case orally as well. In my state, there are seven Justices who hear all the arguments, and each of them can, and often does, interrupt the attorneys at any point during their argument to ask any question he or she chooses to ask at that moment. The attorney must immediately stop what she was saying, perhaps mid-word, and pivot on a dime to answer the question asked, as well as any follow-up question asked by that same Justice, or any of the others. I'm not kidding - that's really how it works, and I live in New Jersey, not Wonderland. In other words: in order to prepare for a state Supreme Court argument, an attorney has to try to anticipate, and be able to answer, just about any rational question about the case that might be thrown her way.

I've done a lot of those state Supreme Court arguments over the years. Almost without exception, during the period of intense preparation leading up to them, I've experienced a moment in which I suddenly realized for the first time what the case was actually about. I'm always stunned by this. How could I possibly have missed it before? And yet, I did.

Revision is about taking your novel to a higher level. It's about knowing your characters so well that you could answer any question about them that anyone could throw at you. Revision teaches you that you were only scratching the surface before. All those things you thought you knew? You hardly knew them at all.

Why is a raven like a writing desk? Beats me. But when is a novel really a novel? When its author could stand up and defend it before the Supreme Court - and win.

No comments:

Post a Comment