Did you think that foodies didn't exist until the 21st century? If that's what you thought, you were very much mistaken. For the 16th-century upper classes, the food that came out of their kitchens had to not only taste delicious; just as importantly, it had to showcase their family's wealth and social status. There were almost always a lot of guests at the table, and it was essential that they give rave reviews about the host's cuisine to everyone they met after they left. Cooking was very much a competitive sport. To give just one example: especially in royal households, meals often ended with what were called "subtleties:" incredibly elaborate sculptures made of sugar or marzipan representing people, animals, or sometimes replicas of buildings. Some of these were edible. Some were not, and in those cases, after all the guests had finished admiring the chef's artistry, they would join in enthusiastically pouncing on the subtlety and destroying it.

The upscale medieval kitchen was a complex place, requiring well-thought-out divisions of labor, much like a modern-day restaurant. Producing three fabulous meals a day, every day, for a family and its associates demanded coordinated efforts from all workers, and the head cook had to have excellent managerial as well as culinary skills. Just to give you an idea, Maria Dembinska's FOOD AND DRINK IN MEDIEVAL POLAND (1963) reports that in the household of the King and Queen of Poland during that era, "the royal entourage normally consisted of forty to sixty people on a daily basis." In addition to the small army of ordinary cooks in their kitchens, "[t]he king and queen also had their own personal cooks. These cooks were accorded very high honor, and as magister coquina (master chefs), they often presented opinions on economic and social matters related to the State."

I'll grant you that in the 1500's there was no Cooking Channel, but that doesn't mean that there weren't at least a few famous chefs. But it wasn't their cooking alone that brought them widespread fame. To achieve that goal, they had to write and publish cookbooks. The most famous European chef of the century was an Italian, Bartolomeo Scappi (c. 1500 - 1577). Little is known of his early life, but by 1536 he was employed by one cardinal, and he went on to work for several others. Then he rose to the top: he moved to the Vatican kitchens where he served two popes, Pius IV and then Pius V. In 1570 he published his life's work: a monumental book called Opera dell'arte del cucinare (something like "culinary works of art"), listing about 1,000 contemporary recipes and describing and illustrating techniques and tools for following them. The first known picture of a fork appears in his pages.

Scappi's cookbook was an instant success, and reprints of it continued to be published for the next 75 years. It was also partially translated into Spanish in 1599 and into Dutch in 1612. When he died, he was buried in the church of Saints Vincenzo and Anastasio alla Regola, which was dedicated to cooks and bakers.

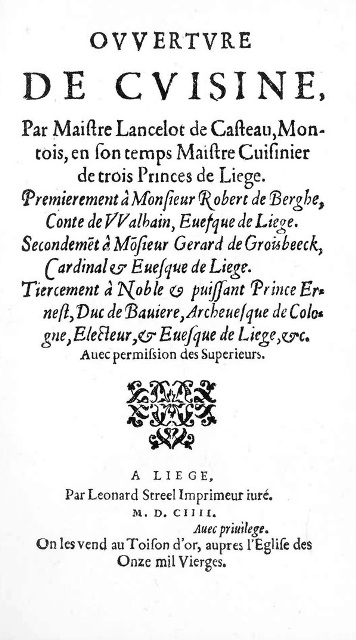

Lancelot de Casteau was a Belgian master-chef who served three prince-bishops of Liege. The first known record of him dates to 1557, when he organized a banquet for the Joyous Entry of Robert of Berghes, the first of his three royal patrons. De Casteau's cooking made him a rich burgher and real-estate owner, but for some reason, the prince-bishops stopped employing him in 1601 and he had to go live with his daughter and son-in-law, who supported him financially. Apparently he began occupying himself with writing a cookbook. His Overture de cuisine, published in 1604, was the first cookbook published in French in the Low Countries, and it served to illustrate the food of the intermediate period between 16th-century cuisine and the haute cuisine of the 17th century. Again, it was the cookbook, and not the cooking per se, that brought De Casteau fame (but not fortune).

Similarly, almost nothing is known of the Englishman Thomas Dawson except that he published several cookbooks during his lifetime, including The Good Huswifes Jewell (1585). The Jewell included not only recipes, but also a catalogue of "approved medicines for sundry diseases," including one for "a tart to provoke courage in either man or woman" which included the brains of male sparrows, and one for a paste of crushed worms to be laid on torn sinews to heal them. (All right, that last part was mildly disgusting, but nothing compared to my "B" post!)

The only contemporary famous female chef I could find was Sabina Welserin, who published the first German-language cookbook in 1553. Almost nothing is known about her except the facts that can be gleaned from her book. Because many of her recipes call for large quantities of spices and sugar, which were hugely expensive and only affordable by the wealthy classes; because some recipes were clearly intended for fancy banquets; and because she mentions that the cook for the Count of Leuchtenberg taught her a method for cooking fish, it's apparent that she was a professional cook and worked for a very wealthy household. I don't know the name of her cookbook, but here is one of her recipes in case you're looking for something to make for dinner tonight:

To make stuffed birds

Prepare them in the following manner: Take small wild birds, hold

Prepare them in the following manner: Take small wild birds, hold

them with a finger and stuff them with eggs. Put some ground anise

and juniper berries into them to avoid a gamy smell. Leave the feet

and heads on the birds, stick them on a spit and roast them, but not too

dry, and in a bowl make a sweet sauce with Reinfal for the birds. In this

manner one can stuff other birds.

Meanwhile, of course, let's not forget that while all this fine dining was going on among the upper classes, the diet of most of the European population consisted almost entirely of coarse bread and pottage (a kind of grain-and-vegetable stew). Often the iron pot containing the pottage would hang over the fire continuously for days. The family would eat from it at mealtimes, and the mother would keep replenishing it with new grains and vegetables. Of course you know this rhyme:

Pease porridge hot, pease porridge cold,

Pease porridge in the pot, nine days old.

It represented reality.