I do love me some Sarah Bird. By which I mean that I love her novels, but I also mean that I have a very strong sense that if I were ever to actually meet her, I would want so badly to be her BFF. Her books glow with wacky humor and deep compassion. Her sharp intelligence enlivens all of her intricate plotlines and their satisfying conclusions. She's one of the handful of authors whose names I periodically Google to see if they've published any new novels, and if they have, I scoop them up. That's how I found out about Bird's ninth novel, ABOVE THE EAST CHINA SEA (Vintage Press, April 2015).

Unlike her other novels, this one didn't draw me in at first. Writers are always told to begin a story with a hook, and I have to admit that a first chapter consisting of a conversation in stylized language between a dead fetus and his dead teenaged mother missed the sweet spot for me by a wide margin. But this was Sarah Bird, so I persevered. I'm glad I did.

We don't learn the name of Tamiko, the pregnant 15-year-old, who lived on Okinawa and died during World War II, until much later in the book, but we do learn a lot about her life before the War. Her two parents exemplify opposite ends of the social spectrum at the time: her mother comes from a long line of pragmatic, rough-mannered Okinawan peasant farmers, while her father's family has long followed white-collar pursuits - mathematics and calligraphy - and considers itself refined and elegant, superior in every way to those who toil in the fields. Tamiko is ashamed of her mother, and ashamed that she takes after her physically: dark skin, round face, broad feet. Her older sister Hatsuko, on the other hand, seems to have inherited more of her father's genes, and is everything Tamiko longs to be: beautiful, graceful, sophisticated. Of course, Hatsuko was selected last year to be one of the Princess Lily girls - the chosen few from the entire island who will be invited to attend the one and only girls' high school. Tamiko is up for the selection process this year, but she has almost no hope for her own prospects and is more or less resigned to her fate - a lifetime of farm work - in advance. But when the war suddenly arrives on Okinawan shores in the form of invading American ships, the old social order is instantly upended.

Switch gears to the book's other story, also set on Okinawa but 70 years after Tamiko's. Luz James is a tough-talking, rule-breaking 17-year-old military brat who pulls off looking like she has her shit together, but secretly contemplatesending it all by jumping off one of the island's high black cliffs. For Luz, Okinawa is just one more in the endless series of her mother's interchangeable short-term postings. At first her mother pumps her up about the prospect of meeting their Okinawan relatives - Luz's maternal grandmother was from the island - but that idea is shut down totally after her mother receives a mysterious letter she refuses to discuss with Luz. So now, the only difference between Okinawa and anyplace else, as far as Luz is concerned, is that this is the first time she's started over in a new place as an only child. When Luz's older sister stunned her by enlisting right out of high school and then promptly getting herself killed on her first deployment, Luz lost the only person who made her feel like she mattered. All she's doing now is going through the motions of hanging out with yet another band of base-kid stoners while trying to decide whether it's even worth the effort. But that begins to change when Luz finds herself trapped in a cave and follows the sound of whimpering until she comes upon a starving, wounded young Okinawan girl who wordlessly begs Luz for help - not for herself, but for her tiny newborn baby. And it changes even more when she leads Jake, the handsome Okinawan boy who follows Luz to the cave because he's worried about her, back to where she saw the girl and her baby. But now, only minutes later, there's nothing there but a pile of bones.

But what's even crazier is how matter-of-factly Jake reacts when Luz can finally bring herself to tell him about the disappearing girl in the cave. "This is Okinawa," he tells her. "This is how it is: We live with the dead and the dead live with us. It's not spooky or creepy or woo-woo; it's just how it is." But what Jake fails to mention at that point is how much more true all of this becomes during the three-day festival of Odon, when the line between the living and the dead becomes so thin that it requires almost no effort to slip across it - in either direction.

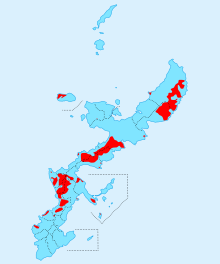

I don't know about you, but my knowledge of Okinawa has, until now, begun and ended with Mr. Miaggi. Wax on, wax off. I didn't know that Japan had used Okinawa as a pawn in World War II, putting it in harm's way and then not even making a pretense of defending it. I didn't know that, despite the fact that Okinawa had no stake in the outcome of the War, something like a third of its population was killed by the end of it. And I didn't know that afterward, part of Japan's peace treaty with the Allied forces was its agreement to cede about one-fifth of Okinawa (which was given no say in the matter) to be used for American military operations.

Or that it didn't matter to the Americans what they were plowing under - fertile fields, ancient burial grounds - in order to build their bases and airstrips. I didn't know that the tiny island of Okinawa has been shamelessly screwed over by more powerful forces, time after time after time.

I was bothered by one gaping plot hole. There's a ton of backstory for all the major players, and a huge emphasis on family, but Luz's absent father barely even gets a mention. Still, to me this omission is heavily outweighed by the sheer pleasure of reading this lovely novel and following its clues until, at the end, the reader fully understands how and why - as the Okinawans say - "life is the treasure."

No comments:

Post a Comment