Abraham Zacuto was born c. 1452 and died sometime between 1510 and 1520, so it might be a bit of a stretch to call him a 16th-century personage, but I've gotten all the way up to Z in this Challenge, barely cheating along the way, so you're just going to have to cut me some slack with this. Thank you. He was a very interesting man, and well worth bending the rules for. The story of his life reads like a well-plotted novel: every good turn of events is followed by a bad one, and vice versa.

Zacuto was born in Salamanca, Spain, into a family of that city's Jewish nobility, and was given an outstanding religious and secular education. As an adult he became a mathematician and astronomer, served as the rabbi of his community, and taught astronomy at several prestigious Spanish universities, becoming quite well-known in academic circles. Unlike Copernicus, whom we discussed for the letter C, Zacuto apparently specialized in applied, rather than theoretical, astronomy. From what little we know, it sounds like the first 40 years of his life were satisfying ones. In 1478 he published, in Hebrew, a "Great Book" of 65 very detailed astronomical tables that corrected a navigational problem no one had been able to overcome before, and was thus of great practical use to seafarers. The book, soon translated into Spanish and Latin versions, became a huge success, and no 16th-century European maritime explorers embarked without a copy of it.

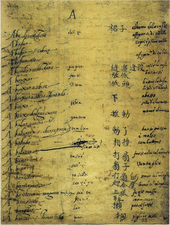

Then all the Jews who refused to convert to Catholicism were expelled from Spain by Ferdinand and Isabella in August 1492, beginning one day before Christopher Columbus embarked on his voyage to the New World with Zacuto's charts on board for guidance (a copy of the charts with Columbus's own handwritten notations is preserved in Seville). Rather than undergo forced conversion (as some historians believe Columbus did, having possibly been born a Jew), Zacuto fled to Portugal, along with tens of thousands of other Jewish refugees. His academic reputation had preceded him and allowed him to land on his feet. He was soon appointed as the Royal Astronomer and Historian to Portugal's King John II.

For most Jewish immigrants to Portugal, their respite (bought from King John with cash) was only temporary; less than a year after granting them asylum, King John ordered that all remaining Jews in the country who refused forced conversions be enslaved. Of course, exceptions were made for valuable citizens like Zacuto, who remained at court in Lisbon. King John died in 1495 and was succeeded by Manuel I, who for a time maintained Zacuto in his royal position and consulted with him as to whether Vasco da Gama's proposed voyage to find a sea route to India would be feasible. Zacuto supported the plan, and he personally trained da Gama and his crew before they departed on their voyage in 1496, bearing with them Zacuto's navigation charts as well as the new, more portable kind of astrolabe he had invented to be used at sea to determine latitude.

But in 1497, bowing to political pressures (he wanted to marry the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, whose views on harboring Jews we all know), King Manuel ordered that the Jews in Portugal must either convert to Christianity or be deported without their children. Zacuto and his son Samuel were among the few who managed to escape the country in safety. They fled first to Tunis, where in 1504 Zacuto wrote a history of the Jewish people from the time of the Creation to the year 1500, which was repeatedly reprinted for centuries afterward. From Tunis, under the increasing threat of Spanish invasion, he moved on to elsewhere in the Middle East - possibly Turkey, possibly Damascus. Exactly where he spent the rest of his life is unknown, but it is said that he was buried in Jerusalem.

The moon crater Zagut is named after Abraham Zacuto.

In THE DISCOVERERS, Daniel Boorstin (my go-to awesome quotemeister) was writing about Jewish cartographers, but I think what he wrote was equally applicable to astronomers like Zacuto, who mapped the skies rather than the Earth: "It was no accident that Jews played a leading role in the liberation of Europeans from the slavery of Christian geography. Driven from place to place, they helped make cartography, still the special preserve of princes and high bureaucrats, into an international science, offering facts equally valid in lands of all faiths. Marginal both to Christians and to Muslims, the Jews became teachers and emissaries bringing Arab learning into the Christian world."

Vermeer: The Astronomer

* * * * * * * *

And thus ends my 2015 A to Z Challenge. It's been an incredible journey for me. I've learned so much, I've made some new cyberfriends, and I feel like I've been part of something meaningful. I'd like to thank the Academy - oops, wrong speech. But I truly would like to thank every blogger who stopped by here during April, even if it was only once, regardless of whether they had time to leave a comment. I started doing this Challenge last year thanks to Yvonne Ventresca, who told me about it. And this year I had the extra satisfaction of being a Minion, which made me feel like I was doing a little bit to give back, even though I didn't have as much time as I would have liked to visit other blogs. There was a comment left on my yesterday's post about how one person can change history, and indeed, that is true. Well, one person, Arlee Bird, thought up this Challenge a few years ago, and look at the amazing thing he's wrought! Bloggers from all around the world come together for one month to share a common goal. The alphabet is, of course, secondary, but it does add a layer of structure and an added element of challenge. Well done, all of us! And that includes everyone who successfully finished as well as everyone who tried but didn't quite make it this time. There's always next year! I hope to see everyone back again in 2016! And until then, here's an Irish blessing that may well date back before my beloved 16th century:

May the road rise to meet you.

May the wind be always at your back;

May the sun shine warm upon your face;

And, until we meet again, may God hold you in the palm of his[/her] hand.

.jpg/355px-Kunyu_Wanguo_Quantu_(%E5%9D%A4%E8%BC%BF%E8%90%AC%E5%9C%8B%E5%85%A8%E5%9C%96).jpg)